Interview with Detmar Leertouwer about the initiation of ‘Bach in Castles’.

Elena Martin, December 2021.

I would like to share an interview Elena Martin (EM) conducted with me (DL) about the launch of my long-term project ‘Bach in Castles’.

EM: Welcome Detmar, and thank you for joining me! It is wonderful that we have some time to speak about your upcoming release of ‘Bach in Castles’. Over the past years I have been a witness, from the sidelines, of your enthusiasm for and dedication and definitely also perseverance for this special project.

Very soon you will release your rendition of Bach’s famous ‘cello suites. Please tell me some more of what is to be expected in due course!

DL: Thank you, Elena, for giving me the opportunity to speak about this project because I do carry it with me already for a long time and it feels like a pregnancy over many years! Even being a man I would describe it like that!

But although you are right that it is the launch of ‘Bach in Castles’, it is not the launch of all the suites by J.S. Bach. In fact it is the launch of the very first suite.

Friday 28th May 2021 was the day that the first movement - the Prelude - of Bach’s first suite in G Major was released on many music streaming platforms like Spotify, Deezer, Tidal, Amazon Music etc.. Apart from the Apple platform, every week between the end of May and the end of June 2021 one movement has been set free. The six movements which comprises the whole Suite.

Apple Music and iTunes will follow later from the 31st December as an album release. All six movements at once. But all this is just the audio part.

The last Friday of this year will also be the release of the video of the whole first suite. And that is the actual real first release of this ‘Bach in Castles’ project.

EM: And please, explain to me the title of your project!

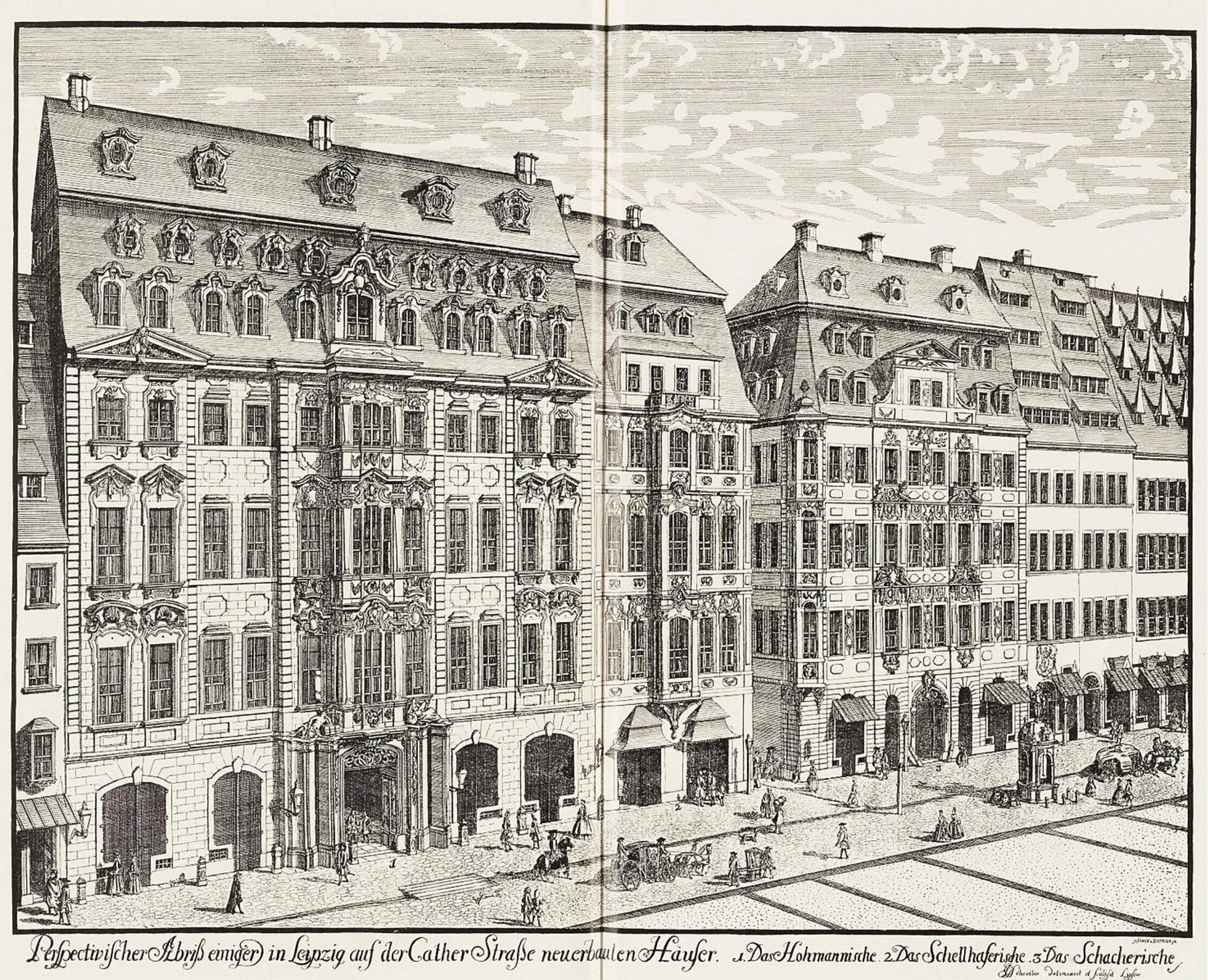

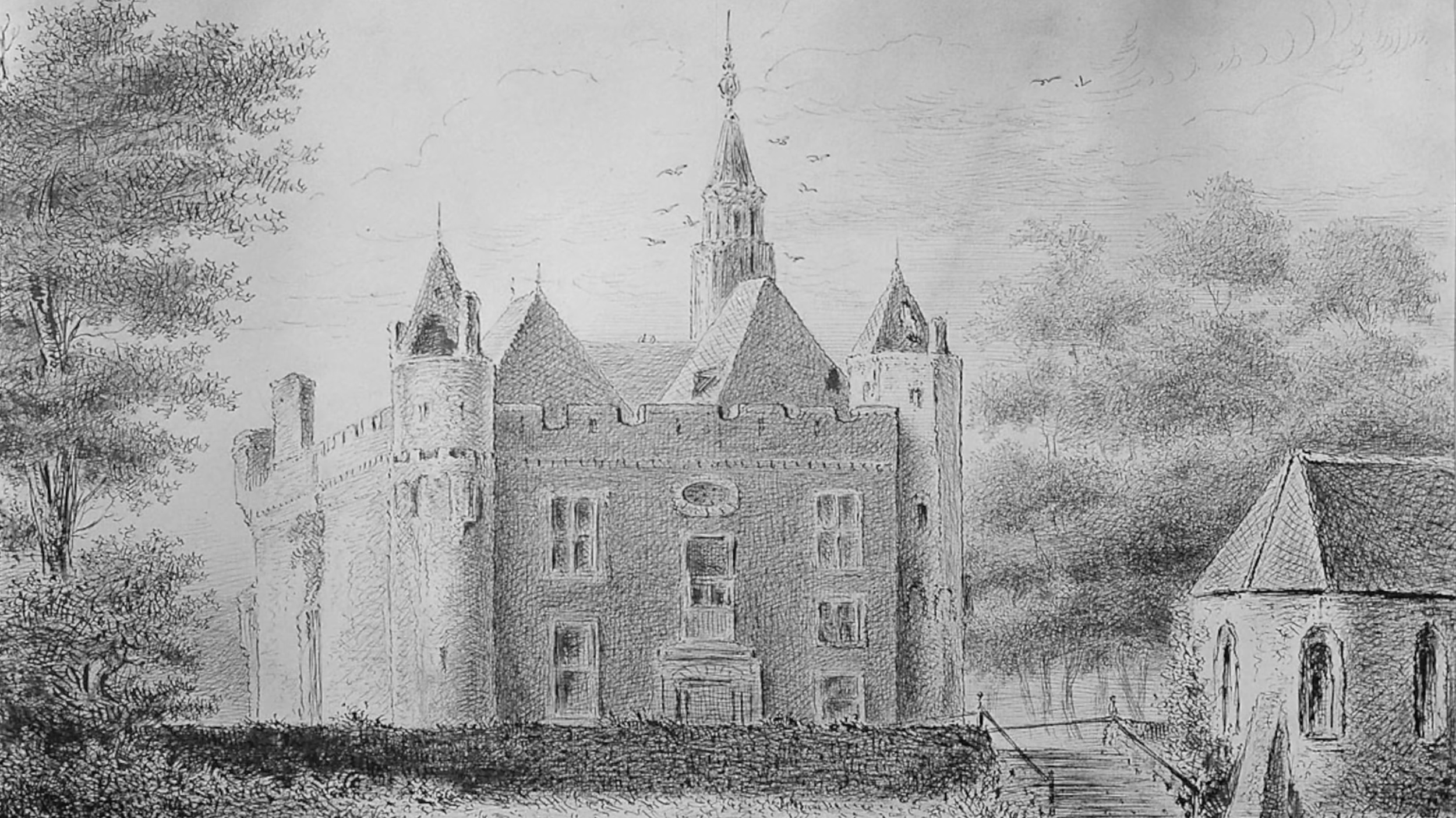

DL: I guess you can imagine from the title in what kind of venue it was recorded. So… yes, in a castle. And more specific in Doornenburg Castle in the East of the Netherlands. More suites will follow in the New Year.

It started like this: I once was allowed to record the Prelude of the first suite in a castle hall. I was not happy with it and thought ‘let’s do this better’. But why not the whole suite instead of only the opening movement? And this became very soon ‘Why not all six suites in six different castles?’.

And the ‘castle idea’?

The first person whom I knew to enthuse for this project was the late Jos van Groeningen from the Nijsinghhuis in Eelde. It later occurred to me that although the Neijsinghhuis is a fantastic place, it was not exactly a castle. More a mansion. So we filmed an other project in his beautiful house.

Nijsinghhuis in Eelde.

Doornenburg Castle (Kasteel Doornenburg).

The people from Doornenburg Castle in the East of the Netherlands offered me their castle as first real castle.

Musicians, colleague ‘cellists often love to play or record in church rooms. They can sound great of course and give a natural reverberation to the sound. And it is inspiring not only to be in a beautiful venue but also to play with the hall and its acoustics. And often musicians love the inspiration of a church as spiritual venue as upbeat for their music or people are excited by the similarity between the architecture of the church construction - for example a big cathedral - and the musical architecture of Bach’s music.

Honestly and historically I think that that is total nonsense in the case of Bach‘s ‘cello suites. Those solo works - and there are many more solo works and instrumental works from that period - were written during Bach’s tenure as Kapellmeister in Cöthen between 1717 and 1723. He did not compose any church music for the court of Cöthen since music was forbidden in the church at this very protestant court. So his whole musical output for the court of Cöthen during this period was strictly for entertainment. And King Leopold von Anhalt-Cöthen did regard Bach highly in that respect.

By the way or on top of this, dance music was definitely forbidden to be performed in a church. And… suites are a chain of dances.

Zimmermannisches Kaffeehaus in Leipzig.

So, Bach’s cello music was not intended to be performed in a church. Rather in a dining hall or the dance hall of a castle. Or in the private quarters of the queen or king or even in the royal bedroom to offer a nice background music before going to sleep. Remember, iPods were not en vogue yet. In those days music was always live-music. An appropriate place for this kind of music by J.S. Bach might also be the pub - like Cafe Zimmerman later in Leipzig - or maybe an university hall. Not the church. Historically seen.

Hence the title ‘Bach in Castles’. A castle as a more likely place to perform a Bach suite than a church.

Of course by no means I think that nowadays you can not perform your Bach suite in a church, but the usual stories to rectify the choice of performing it in a church are humbug.

And don’t misunderstand me, a very important part of Bach’s works does belong in the church!

EM: Detmar, you use a baroque ‘cello for your registration of the Bach ‘cello suites. Why you would use a baroque ‘cello or what it actually is, is maybe not common knowledge to everyone. Could you tell us about your choice for a baroque instrument?

DL: That is an interesting thing to speak about in this context.

The violoncello as it looks and sounds today is quite a different instrument from the instrument Bach knew as violoncello.

Usually musicians are modest people and don’t say that they know better than the composer how to perform their music. So they actually want to follow the ‘guidelines’, as far as there are any, of the composer and not just do whatever they like to do or whatever comes to mind. For me personally that means that I try to assemble a picture of how music in the time or surroundings of Bach for instance, might have sounded. There are of course no recordings so we have to do it with accounts of musical events, sometimes pedagogical works, paintings, writings by the composers themselves and the instruments of those days. And they can be pretty different from the way we know them today. This kind of research or study can become very profound and as musicians we can profit from the work and digging musicologists did for us.

For me this is the starting point for interpreting music after of course the sheer notes of a score. Is it a work from 1656 or from 1965? In other words, the context.

In this way I feel that I can come the closest to the intentions of a composer as long as I can not speak with him or her and as long as the composer did not leave detailed instructions or background information about a particular work.

Probably every musician would state that bringing out the true intention of the creator of a work, is what he tries to do.

But then there is the question about the instrument.

With a baroque ‘cello the fingerboard, the piece of wood where you touch the ‘cello with your fingers, is shorter. There is no endpin. The strings are made of gut instead of steel or nylon. The bridge, the piece of blank wood holding the strings in the middle of the ‘cello, is differently cut. In the case of my baroque ‘cello, it is thicker and lower than on my modern instrument. The pieces of wood on the inside of the instrument tend to be lighter.

Baroque ‘cello.

The ‘cello today (endpin is normally pulled out).

Nowadays are days of standardisation or fixed standards. In the 17th and 18th century everything about violin making (‘cello making) was still flexible and developing. The urges for standardised forms became more and more important from the middle of the 18th century. That is also the time of ‘bundling knowledge’ (the first encyclopaedias) and the rise of tutorial material.

So in the 17th and 18th century ‘violoncello’ did not mean the one instrument we know now. It could mean a range of instruments with different sets of strings or tuning, different measurements - often larger than today - , different playing manners. It depends where and when you look. The papal court in Rome is something else than a North German church community or court. France? Yet an other world. I don’t even dive into the subject of the ‘proper’ naming of the instrument now. That is partly still an area of dispute or at least confusion.

To keep it simple, my baroque ‘cello is larger and especially broader and thicker than the modern sister. The neck is fatter and less angled which gives less tension to the strings. Therefore it sounds more free and more resonant but possibly not as loud as a modern instrument. And… it is tuned lower. The A-string on my baroque ‘cello sounds one whole tone lower than the ‘modern A’.

So much for the visual aspects of the baroque instrument in comparison to what a ‘cello nowadays looks like.

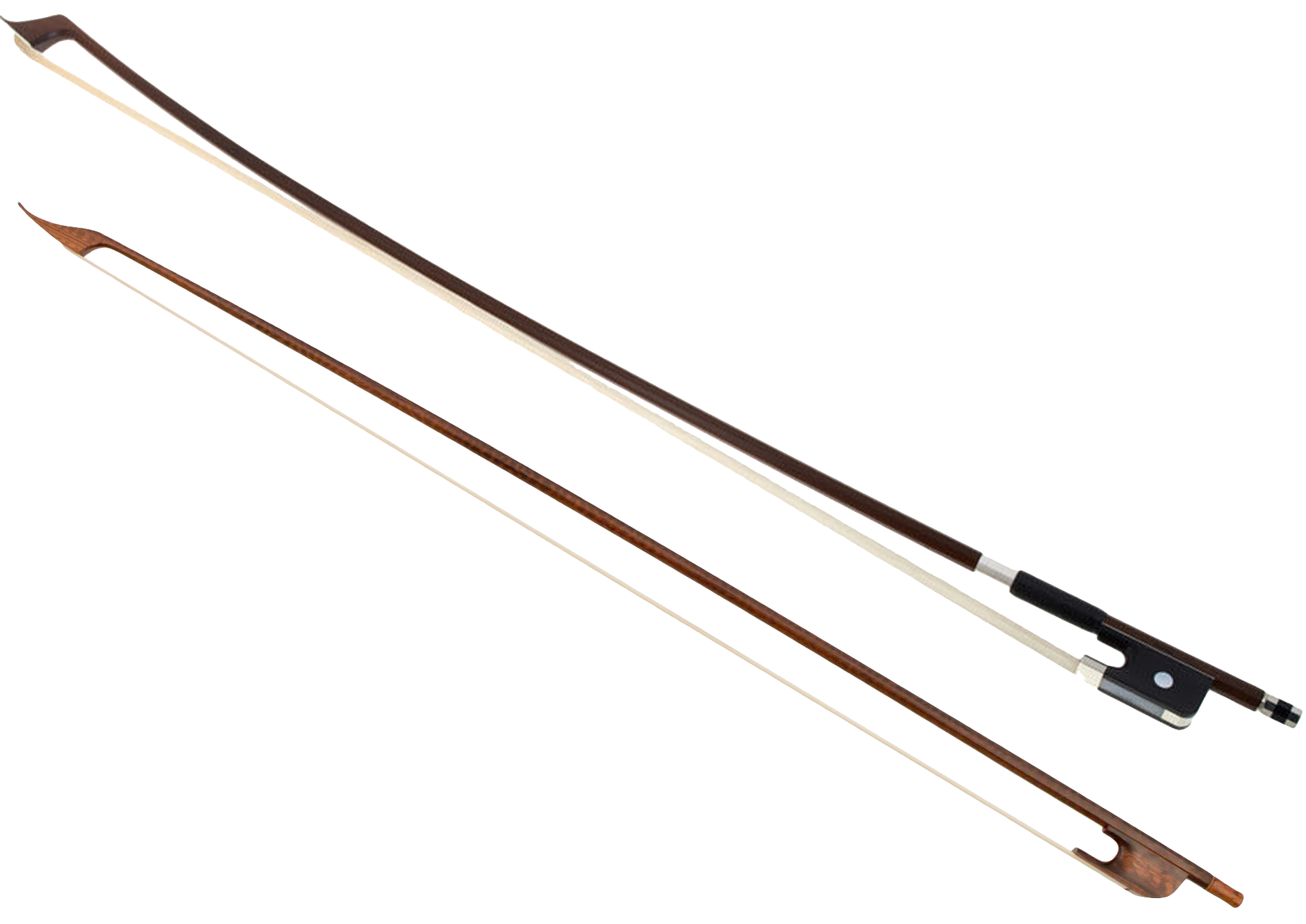

There is also the issue of the bow.

The modern bow is concave and heavier, also heavier at the tip. The baroque bow is convex - like a bow and arrow - and lighter (at the tip).

A modern bow on top and a baroque bow below.

All this, together with a different style of playing, makes the baroque ‘cello sound dramatically different from the modern ‘cello today. But it probably comes much closer to what a baroque composer, in this case Bach, had in mind as a ‘cello sound.

EM: So you use the baroque ‘cello because it is closer to the idea of Bach or the way he knew a ‘cello sounds?

DL: Yes exactly. That is how I think I can pay tribute to Bach’s music the best.

The best as a starting point, because very important or maybe even more important than the choice of instrument is in the end how you bring the music to life. And with the right language you can come to quite a good end even on a modern instrument.

There is one thing I like to mention. The further we get away from the origin of a piece by sheer time difference, the more beautiful we tend to play it. But I think that in the course of time we lose some of the original vibe and often we start to celebrate only the beauty aspect of the music. For example, listen to those exciting premiere performances of Rostropovich in the Tsjaikovski Hall in Moscow in the sixties. Live-performances, not overly polished but so lively and vibrant. Today many a young ‘cellist can play the same - let’s say - first Shostakovich concerto, very well practiced with beautiful sound and everything works perfectly smooth. But for me personally no comparison to Rostropovich’s first performances from the end of the fifties.

Take that idea 150 years back from the Shostakovich example and imagine how an original Beethoven performance would have sounded. Of course there are no recordings but there exist many accounts of how Beethoven played and acted as human being. It must have been anything else than a perfect balanced, well prepared and polished Beethoven Steinway recital.

A more recent example is when you compare the live performances - recorded though - of Piazzolla with his own music and the later recordings from musicians who love to perform his music. It often misses that original groove but does sound BEAUTIFUL.

So within the original setting, as far as I can grasp it in the case of Bach, I do not mind a certain rough edge to it. But of course within that ‘rougher’ framework I try to find the highest beauty.

EM: I had a peak view into your Bach video. I find it much more than only a performing registration in an interesting venue. Could you elaborate a bit on this?

DL: This very first video I made, which I dismissed later although it is still somewhere on YouTube, was only a playing registration. But once I was granted access to the Nijsinghhuis and saw its beauty and originality it became clear to me that it would not be interesting to produce a video in which you see a lonely artist at work during the whole video. There are so many concert registrations like this. I was certain to include a lot of the surroundings of the place in the video.

So to answer your question, like in ‘Fantasia for ‘Cello Alone’ you also see in ‘Bach in Castles’ a lot of the place, the garden, around the castles, the barbicans, the kitchen etc..

Of course every castle offers different things to film and include. We do try to avoid modern elements like cars, telephones posts, a modern grand piano, flat screen panels for tourist purposes etc.. So we did have to film around things a bit. In some castles this is less a problem than in other places. But in one of the castles we also include the modern art which is an integral part of the place since the owner of the castle is a contemporary artist.

EM: This release is the first of six videos?

DL: Exactly, it is a 6 part video project released one by one. This first suite is recorded in Doornenburg Castle in the Netherlands near Germany. We filmed or will record in a few more castles in the Netherlands, in Germany as well as in Switzerland.

EM: If I am right there are more ideas embedded in your project than only a fancy place to perform, aren’t there?

DL: One of the ideas, since I am using a baroque instrument and try to come as close to how it might have sounded 300 years ago I also experiment with different bow holds or bow grips. Also this was not as standardized as it is more or less today. I am referring to where and partly how to hold the bow.

Michel Corrette shows in a description from 1741 three ways to hold the bow. The first position is the way the Italians tended to do: four fingers on the stick a bit towards the middle of the bow with the thumb and the little finger touching the wood (fingers at A, B, C and D in the drawing below).

Then there are two ways a ‘cellist in France would hold the bow: at the same place as before but with the thumb under the hair and the pinky under the stick (F and G in the drawing). The second manner in France is with the hand more towards the right part of the bow (H, I, K), the thumb under the wood part - the frog (L) - and the pinky on the stick (M).

But there is actually a fourth manner to conduct the bow and that is the so-called underhand grip, the way a viola da gamba player would hold the bow.

The ‘cellist depicted in the black-and-white picture is of course a musician in the 17th century.

Nevertheless this bow hold was still in use seventy to hundred years later during Bach’s life span (1685-1750) and even later in Germany and for example in the Netherlands or England.

Close-up of an underhand grip.

‘Thumb-under-the-frog’ bow grip.

I try to include these different bow grips throughout my suites series.

So in the first suite, which will be out soon, I apply the French ‘under-the-frog’ grip.